Sanghanayaka Suddhananda Mahathero

Buddhist Philosophy, Culture, Traditions and History Sanghanayaka Suddhananda Mahathero

Dhaka, Bangladesh (15 January 1933 – 3 March 2020)

Introduction

The story of Buddhism might be said to have begun with a loss of innocence. Siddhartha Gautama, a young prince of the Shakhya clan in India, was born in the 6th century BCE, a time of great turmoil and political change in India; many were unsatisfied with the Vedic religion, and new teachings had emerged, among them the Upanishads. The Buddha stood largely outside the Vedic tradition, criticizing many of its central teachings. Nevertheless, he had been influenced by that tradition and his teachings in turn would have a profound effect on later teachers in the Hindu tradition, such as Shankara; even in such Hindu classics as the Bhagavad Gita, some reaction can be seen to Buddhist teachings. But later centuries would see Buddha’s influence wane in India and instead spread to other Asian countries. Today, Buddhism has spread throughout the world. Various sects have arisen as later teachers have reinterpreted and expounded upon the Buddha’s basic teachings. Buddhism may be considered a religion, a philosophy, a way of life, or all three; here we will deal mainly with Buddhism as a philosophical system.

Metaphysics

The Buddha’s main concern was to eliminate suffering, to find a cure for the pain of human existence. In this respect, he has been compared to a physician, and his teaching have been compared to a medical or psychological prescription. Like a physician, he observed the symptoms – the disease that human kind was suffering from; next he gave a diagnosis – the cause of the disease; then he gave the prognosis – it could be cured; finally, he gave the prescription – the method by which the condition could be cured.

His first teaching, the Four Noble Truths, follows this pattern. First, the insight that “life is dukkha.” Dukkha is variously translated as suffering, pain, impermanence; it is the unsatisfactory quality of life which is targeted here – life is often beset with sorrow and trouble, and even at its best, is never completely fulfilling. We always want more happiness, less pain. But this ‘wanting more’ is itself the problem: the second noble truth teaches that the pain of life is caused by ‘tanha’ – our cravings, our attachments, our selfish grasping after pleasure and avoiding pain. Is there something else possible? The third noble truth says yes; a complete release from attachment and dukkha is possible, a liberation from pain and rebirth. The fourth noble truth tells how to attain this liberation; it describes the Noble Eightfold Path leading to Nirvana, the utter extinction of the pain of existence.

Another main teaching of Buddhist metaphysics is known as the Three Marks of Existence. The first is Anicca, impermanence: all things are transitory, nothing lasts. The second is Anatta, No-Self or No-Soul: human beings, and all of existence, is without a soul or self. There is no eternal, unchanging part of us, like the Hindu idea of Atman; there is no eternal, unchanging aspect of the universe, like the Hindu idea of Brahman. The entire idea of self is seen as an illusion, one which causes immeasurable suffering; this false idea gives rise to the consequent tendency to try to protect the self or ego and to preserve its interests, which is futile since nothing is permanent anyway. The third mark of existence is that of Dukkha, suffering: all of existence, not just human existence but even the highest states of meditation, are forms of suffering, ultimately inadequate and unsatisfactory.

The three marks of existence can be seen as the basis for the four noble truths above; in turn the three marks of existence may be seen to come out of an even more fundamental Buddhist theory, that of Pratityasamutpada: Dependent Origination, or Interdependent Co-arising. This theory says that all things are cause and are caused by other things; all of existence is conditioned, nothing exists independently, and there is no First Cause. There was no beginning to the chain of causality; it is useless to speculate how phenomenal existence started. However, it can be ended, and that is the ultimate goal of Buddhism – the ultimate liberation of all creatures from the pain of existence.

Sometimes this causality is spoken of as a circular linking of twelve different factors; if the chain of causality can be broken, existence is ended and liberation attained. One of these factors is attachment or craving, tanha, and another is ignorance; these two are emphasized as being the weak links in the chain, the place to make a break. To overcome selfish craving, one cultivates the heart through compassion; to eliminate ignorance one cultivates the mind through wisdom. Compassion and wisdom are twin virtues in Buddhism, and are cultured by ethical behavior and meditation, respectively. It is a process of self-discipline and self-development, which emphasizes the heart and mind equally, and insists that both working together are necessary for enlightenment. In keeping with the ideas of dependent origination, Buddhism views a person as a changing configuration of five factors, or ‘skandhas.’ First there is the world of physical form; the body and all material objects, including the sense organs. Second there is the factor of sensation or feeling; here are found the five senses as well as mind, which in Buddhism is considered a sense organ. The mind senses thoughts and ideas much the same as the eye senses light or the ear senses air pressure. Thirdly, there is the factor of perception; here is the faculty which recognizes physical and mental objects. Fourth there is the factor variously called impulses or mental formulations; here is volition and attention, the faculty of will, the force of habits. Lastly, there is the faculty of consciousness or awareness. In Buddhism consciousness is not something apart from the other factors, but rather interacting with them and dependent on them for its existence; there is no arising of consciousness without conditions. Here we see no idea of personhood as constancy, but rather a fleeting, changing assortment or process of various interacting factors. A major aim of Buddhism is first to become aware of this process, and then to eliminate it by eradicating its causes.

This process does not terminate with the dissolution of the physical body upon death; Buddhism assumes reincarnation. Even though there is no soul to continue after death, the five skandhas are seen as continuing on, powered by past karma, and resulting in rebirth. Karma in Buddhism, as in Hinduism, stems from volitional action and results in good or bad effects in this or a future life. Buddhism explains the karmic mechanism a bit differently; it is not the results of the action per se that result in karma, but rather the state of mind of the person performing the action. Here again, Buddhism tends to focus on psychological insights; the problem with bad or selfish action is that it molds our personality, creates ruts or habitual patterns of thinking and feeling. These patterns in turn result in the effects of karma in our lives.

Many other metaphysical questions were put to the Buddha during his life; he did not answer them all. He eschewed the more abstract and speculative metaphysical pondering, and discouraged such questions as hindrances on the path. Such questions as what is Nirvana like, what preceded existence, etc., were often met by silence or what may have seemed like mysterious obscurity. Asked what happens to an Arhant, an enlightened one, upon his death, the Buddha was said to have replied: “What happens to the footprints of the birds in the air.” Nirvana means ‘extinction’ and he likened the death of an Arhant to the extinction of a flame when the fuel (karma) runs out. He evidently felt that many such questions were arising out of a false attachment to self, and that they distracted one from the main business of eliminating suffering.

Philosophy

The Buddha intended his philosophy to be a practical one, aimed at the happiness of all creatures. While he outlined his metaphysics, he did not expect anyone to accept this on faith but rather to verify the insights for themselves; his emphasis was always on seeing clearly and understanding. To achieve this, however, requires a disciplined life and a clear commitment to liberation; the Buddha laid out a clear path to the goal and also observations on how to live life wisely. The core of this teaching is contained in the Noble Eightfold Path, which covers the three essential areas of Buddhist practice: ethical conduct, mental discipline (‘concentration’ or ‘meditation’), and wisdom. The goals are to cultivate both wisdom and compassion; then these qualities together will enable one ultimately to attain enlightenment.

Regarding the Buddhist path as a philosophy, one may consider its epistemology: certain claims of knowledge have been made, but how can they be known to be true? As stated above, the Buddha himself never asked anyone to accept unproven claims on faith, and in fact discouraged them from doing so. He maintained that his teachings could be verified by direct insight and reasoning, by anyone willing to consider them and to follow the necessary path of self-discipline. Starting from a few basic assumptions, such as impermanence and dependent origination, he derived a complex and consistent system of philosophy which has stood for centuries. Later teachers have validated his claim that others could reach the same insights, and they have expanded upon his basic teachings with impressive intuitive depth and intellectual rigor.

In this way the Buddhist teaching has itself become a kind of interactive and self-evolving process, much like its idea of pratityasamutpada. However, the end goal is still Nirvana, which is an experience ultimately beyond all concepts and language, even beyond the Buddhist teachings. In the end even the attachment to the Dharma, the Buddhist teaching, must be dropped like all other attachments. The tradition compares the teaching to a raft upon which one crosses a swift river to get to the other side; once one is on the far shore, there is no longer any need to carry the raft. The far shore is Nirvana, and it is also said that when one arrives, one can see quite clearly that there was never any river at all.

Culture

Culture reveals to ourselves and others what we are. It gives expression to our nature in our manner of living and of thinking, in art, religion, ethical aspirations, and knowledge. Broadly speaking, it represents our ends in contrast to means.

A cultured man has grown, for culture comes from a word meaning “to grow.” In Buddhism the arahant is the perfect embodiment of culture. He has grown to the apex, to the highest possible limit, of human evolution. He has emptied himself of all selfishness – all greed, hatred, and delusion – and embodies flawless purity and selfless compassionate service. Things of the world do not tempt him, for he is free from the bondage of selfishness and passions. He makes no compromises for the sake of power, individual or collective.

In this world some are born great while others have greatness thrust on them. But in the Buddha-Dhamma one becomes great only to the extent that one has progressed in ethical discipline and mental culture, and thereby freed the mind of self and all that it implies. True greatness, then, is proportional to one’s success in unfolding the perfection dormant in human nature.

We should therefore think of culture in this way: Beginning with the regular observance of the Five Precepts, positively and negatively, we gradually reduce our greed and hatred. Simultaneously, we develop good habits of kindness and compassion, honesty and truthfulness, chastity and heedfulness. Steady, wholesome habits are the basis of good character, without which no culture is possible. Then, little by little, we become great and cultured Buddhists. Such a person is rightly trained in body, speech, and mind — a disciplined, well-bred, refined, humane human being, able to live in peace and harmony with himself and others. And this indeed is Dhamma.

Tradition and History

The history of the Buddhism begins with the enlightenment of the Buddha. At the age of thirty-five, he awakened from the sleep of delusion that grips all beings in an endless vicious cycle of ignorance and unnecessary suffering (around 528 BCE). Having awakened, he decided to “go against the current” and communicate his liberating wakefulness to suffering beings—that is, to teach the Dharma.

For forty-five years, he crossed and re-crossed central India on foot conveying his profound, brilliant wakefulness directly as well as by means of explanations that grew into a great body of spiritual, psychological, and practical doctrine. His enlightenment as well as the doctrine leading to it have been passed down through numerous unbroken lineages of teachers, which have spread to many countries. Many of these lineages still flourish.

At the time of the Buddha’s death, his Dharma was well established in central India. There were many lay followers, but the heart of the Dharma community were the monastics, many of whom were arhats. Numerous monasteries had already been built round about such large cities as Rajagriha, Shravasti, and Vaishali.

The first to assume the Buddha’s mantle, tradition tells, was his disciple Mahakashyapa, who had the duty of establishing an authoritative version of the Buddha’s teachings. Thus, during the first rainy season after the Buddha’s death (parinirvana), Mahakashyapa convoked an assembly of five hundred arhats. At this assembly, it is said, Ananda, the Buddha’s personal attendant, recited all of the master’s discourses (sutras), naming the place where each was given and describing the circumstances.

A monk named Upali recited all the rules and procedures the Buddha had established for the conduct of monastic life. Mahakashyapa himself recited the matrika, lists of terms organized to provide analytical synopses of the teachings given in the sutras. These three extensive recitations, reviewed and verified by the assembly, became the basis for the

Sutra Pitaka (Discourse Basket), the Vinaya Pitaka (Discipline Basket), and Abhidharma Pitaka (Special Teachings Basket), respectively. The Tripitaka (all three together) is the core of the Buddhist scriptures. This assembly, held at Rajagriha with the patronage of the Magadhan king Ajatashatru, is called the First Council.

In the early centuries after the Buddha’s death, the Buddha Dharma spread throughout India and became a main force in the life of its peoples. Its strength lay in its realized (arhat) teachers and large monasteries that sheltered highly developed spiritual and intellectual communities. Monks traveled frequently between the monasteries, binding them into a powerful network.

As the Dharma spread to different parts of India, differences emerged, particularly regarding the Vinaya, or rules of conduct. Roughly a hundred years after the First Council, such discrepancies led to a Second Council in Vaishali, in which seven hundred arhats censured ten points of lax conduct on the part of the local monks, notably the acceptance of donations of gold and silver. In spite of this council and other efforts to maintain unity, gradually, perhaps primarily because of size alone, the Sangha divided into divergent schools.

Among the principal schools was a conservative faction, the Sthaviravada (way of the elders), which held firmly to the old monastic ideal with the arhat at its center and to the original teaching of the Buddha as expressed in the Tripitaka. Another school, the Mahasanghikas, asserted the fallibility of arhats. It sought to weaken the authority of the monastic elite and open the Dharma gates to the lay community. In this, as well as in certain metaphysical doctrines, the Mahasanghikas prefigured the Mahayana.

Another important school was that of the Sarvastivadins (from Sanskrit sarva asti, “all exists”), who held the divergent view that past, present, and future realities all exist. In all, eighteen schools with varying shades of opinion on points of doctrine or discipline developed by the end of the third century BCE. However, all considered themselves part of the spiritual family of the Buddha and in general were accepted as such by the others. It was not rare for monks of different schools to live or travel together.

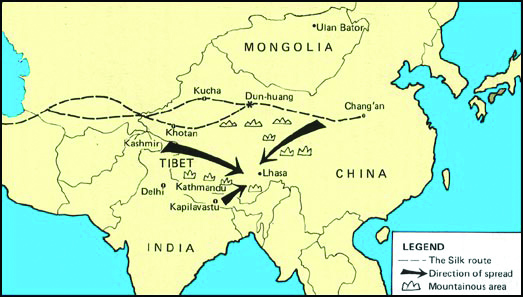

King Ashoka was the third emperor of the Mauryan empire, which covered all of the Indian subcontinent but its southern tip. His personal espousal of the Dharma and adoption of its principles for the governance of his immense realm meant a quantum leap in the spread of the Buddha’s teaching. The imperial government promulgated the teachings. It supported the monasteries and sent proselytizing missions to the Hellenic states of the northwest and to Southeast Asia. Under King Ashoka, institutions of compassion and nonviolence were established throughout much of India. These include peaceful relations with all neighboring states, hospitals and animal hospitals, special officials to oversee the welfare of local populations, and shady rest stops for travelers. Thus he remains today the paragon of a Buddhist ruler, and his reign is looked back upon by Buddhists as a golden age. Under his patronage, a Fourth Council was held, at which major new commentaries on the Tripitaka were written, largely under Sarvastivadin influence. Under Kanishka, the Buddha Dharma was firmly planted among the Central Asian peoples whose homelands lay along the Silk Route, whence the way lay open to China. The Kushan empire also saw the flowering of Gandharan art, which under Hellenistic influences produced Buddha images of extraordinary nobility and beauty.

Traditional accounts of the Fourth Council say that the assembly was composed of arhats under the leadership of the arhat Parshva but also under the accomplished bodhisattva Vasumitra. Indeed, it was at this time, about the beginning of the second century, that the way of the bodhisattva, or the Mahayana (Great Vehicle), appeared. It was this form of the Buddha Dharma that was to conquer the north, including China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, and Mongolia.

The most visible manifestation of the Mahayana was a new wave of sutras, scriptures claiming to be the word of the Buddha that had remained hidden until then in other realms of existence. The Mahayana replaced the ideal of the arhat with that of the bodhisattva. Whereas arhats sought to end confusion in themselves in order to escape samsara, bodhisattvas vowed to end confusion in themselves yet remain in samsara to liberate all other sentient beings. The vision of spiritual life broadened beyond the controlled circumstances of cloister and study to include the wide-open situations of the world.

Correspondingly, the notion of “buddha” was no longer limited to a series of historical personages, the last of whom was Shakyamuni [Siddhartha Gautama], but referred also to a fundamental self-existing principle of spiritual wakefulness or enlightenment. While continuing to accept the old Tripitaka, Mahayanists regarded it as a restricted expression of the Buddha’s teaching, and they characterized those who held to it exclusively as Hinayanists (adherents of the Hinayana, the Small Vehicle).

Great masters shaped the Mahayana in the early centuries of the common era. Outstanding among them all was Nagarjuna (fl. second or third century), whose name connects him with the nagas (serpent deities) from whose hidden realm he is said to have retrieved the Prajnaparamita sutras, foundational Mahayana scriptures.

Through most of the Gupta period the Buddha Dharma flourished unhindered in India. In the sixth century, however, hundreds of Buddhist monasteries were destroyed by invading Huns under King Mihirakula. This was a serious blow, but the Dharma revived and flourished once again, mainly in northeastern India under the Pala kings (eighth-twelfth centuries). These Buddhist kings patronized the monasteries and built new scholastic centers such as Odantapuri near the Ganges some miles east of Nalanda. Though the Hinayana had largely vanished from India by the seventh century, in this last Indian period the Mahayana continued, and yet another form – known as Mantrayana, Vajrayana, or Tantra – became dominant.

Like the Mahayana, the Vajrayana was based on a class of scriptures ultimately attributed to the Buddha, in this case known as Tantras. Vajrayanists regarded the Hinayana and Mahayana as successive stages on the way to the tantric level. The Vajrayana leaped yet further than the Mahayana in acceptance of the world, holding that all experiences, including the sensual, are sacred manifestations of awakened mind, the buddha principle. It emphasized liturgical methods of meditation, or sadhanas, in which the practitioner identified with deities symbolizing various aspects of awakened mind. The palace of the deity, identical with the phenomenal world as a whole, was known as a mandala. In the place of the arhat and the bodhisattva, the Vajrayana placed the siddha, the realized tantric master.

By the 13th century, largely as a result of violent suppression by Islamic conquerors, the Buddha Dharma was practically extinct in the land of its birth. However, by this time Hinayana forms were firmly ensconced in Southeast Asia, and varieties of Mahayana and Vajrayana in most of the rest of Asia.

Spread of Buddhism in Asian countries

In Sri Lanka during the third century BCE, King Devanampiya Tissa turned to Theravada Buddhism. The Sinhalese king built the Mahavihara monastery and there enshrined a branch of the Bodhi Tree that had been brought from India. For more than two millennia since that time, the Mahavihara has been a powerful force in the Buddhism of Ceylon and other countries of Southeast Asia, notably Burma and Thailand. The Theravada in Ceylon remains the oldest continuous Dharma tradition anywhere in the world. Emissaries sent by King Ashoka in the third century BCE first brought the Dharma to Burma. By the fifth century, the Theravada was well-established, and by the seventh century the Mahayana had appeared in regions near the Chinese border. By the eighth century, the Vajrayana was also present, and all three forms continued to coexist until King Anaratha established the Theravada throughout the land in the eleventh century. Pagan, the royal capital in the north, adorned with thousands upon thousands of Buddhist stupas and temples, and was the principal bastion of Buddha Dharma on earth until sacked by the Mongols in 1287. In succeeding centuries the Theravada continued strong, interacting closely at times with the Dharma centers of Ceylon The Burmese form of Theravada acquired a unique flavor through its assimilation of folk beliefs connected with spirits of all kinds known as nats. Today 85 percent of Burmese are Buddhist, and Buddhism is the official religion of the country.

Buddha Dharma’s golden age in China was the T’ang period. Monasteries were numerous and powerful and had the support of the emperors. Buddhism came to Korea from China in the fourth century CE. It flourished after the Silla unification in the seventh century. The Buddha Dharma was brought to Japan from Korea in 522. It received its major impetus from the regent prince Shotoku, a Japanese Ashoka. The Buddha Dharma of Tibet (and Himalayan countries such as Sikkim, Bhutan, and Ladakh) preserved and developed the Vajrayana tradition of late Indian Buddhism and joined it with the Sarvastivadin monastic rule. The Mongols were definitively converted to Tibetan Buddhism in the sixteenth century. Scriptures and liturgies were translated into Mongolian, and the four principal Tibetan schools flourished until the Communist takeover of the twentieth century. Vietnam lay under Chinese influence, and the Chinese Mahayana sects of Ch’an (Thien) and Pure Land (Tindo) were well established in the country by the end of the first millennium. Theravada was introduced b the Khmers but remained largely confined to areas along the Cambodian border. The Buddhism of the Sarvastivadin school spread to Cambodia in the third century BCE and reached a high point in the fifth and sixth centuries. From the eleventh century, Hinduist Khmers were a major factor in many regions of the country. In the thirteenth century, however, the Thai royal house established Theravada Buddhism as the national religion.

Conclusion

The Buddhist tradition is most clearly associated with non-violence and the principle of ahimsa (“no harm”). By eliminating their attachments to material things, Buddhists try to combat covetousness, which in itself has the potential to become a source of anger and violence against others. In reality, at our innermost cores we are all exactly the same: we are human beings who wish to have happiness and to avoid suffering. Yet, out of ignorance, we go about seeking these goals blindly and without insight. We live our lives seemingly oblivious to our own prejudices even though they are right in front of our eyes. In short, we suffer because we embrace the mistaken notion of our separateness from one another. Only Buddha’s teachings are the solutions of all sufferings.

This article is being concluded by paying deepest homage to Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, Lobzang Thupstan Chognor, the world renowned Prince, Buddhist monk, social activist, statesman and diplomat and Ven. J. Gombojav, Khambo Lama of Mongolia who extended memorable services for world peace through establishing the Asian Buddhists Conference for Peace.

May all sentient beings be happy.

____________________________________

The late writer was the Supreme Patriarch of Mahanikaya Buddhists of Bangladesh, President of Bangladesh Bouddha Kristi Prachar Sangha and President of A.B.C.P Bangladesh National Chapter.

Contact Us

- Da Lama Kh.Byambajav, Secretary General of ABCP, Gandantegchenling Monastery, Ulaanbaatar-38, Mongolia 16040

- abcphqrs@gmail.com

- +976 11 360069, +976 99117415

- Mr. Burenbayar Chanrav, Senior Manager, ABCP, Gandantegchenling Monastery, Ulaanbaatar-38, Mongolia 16040

- cburenbayar@gmail.com

- +976-99101871

Newsletter

You can trust us. we only send promo offers,