Introduction

Nestled in the foothills of the Dhauladhar mountain range in Himachal Pradesh, India, Dharamshala is more than just a picturesque hill station. Since 1960, it has become the spiritual and political center of the Tibetan diaspora and the residence of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. Often referred to as Little Lhasa, this small Himalayan town has been transformed into a sacred Karmabhūmi, a field of virtuous action, by His Holiness, who turned a refugee settlement into a global epicenter of Buddhist learning, interfaith dialogue, and cultural resilience. Dharamshala is located in the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, in the district of Kangra. Perched at an elevation ranging from 1,250 to 2,000 meters, the town is divided into Lower Dharamshala, the administrative and commercial hub, and Upper Dharamshala, or McLeod Ganj, which hosts the Tibetan community and the residence of the Dalai Lama. The region is surrounded by dense coniferous forests, snow-capped mountains, and pristine valleys, offering a serene environment conducive to spiritual retreat and meditation (Kapadia 104). Historically, Dharamshala was part of the ancient Trigarta kingdom and later came under the influence of the British colonial administration. It became a military cantonment in the mid-19th century. The devastating Kangra earthquake of 1905 significantly damaged the town, leading to a period of decline (Bansal 45). However, it was not until the arrival of the Dalai Lama in the late 1950s that Dharamshala would assume its modern identity as a global center of Tibetan Buddhism and intercultural diplomacy. This article explores the geographical setting and historical roots of Dharamshala, the Dalai Lama’s arrival and transformative impact, the major institutions he established, and its significance as a moral and spiritual center not only for Tibetans but also for Buddhists and peace advocates worldwide along with his contribution in reinvigorating sacred heritage and Nalanda Tradition.

The Dalai Lama’s Arrival and the Birth of Little Lhasa

Following the brutal Chinese suppression of the Tibetan uprising in 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India with approximately 80,000 Tibetan refugees. He was granted political asylum by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and in 1960, the Indian government offered Dharamshala as the site for the Tibetan government-in-exile, officially known as the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) (Thurman 68). Since then, Dharamshala has served as the de facto capital of the Tibetan diaspora. The Dalai Lama’s arrival marked the beginning of a profound transformation. In a town that had been relatively obscure on the global stage, His Holiness established both the seat of political resistance and the heart of spiritual resilience. Tibetan settlements, schools, temples, and monasteries began to spring up around McLeod Ganj, earning it the nickname “Little Lhasa”, a poignant reference to the lost homeland of Tibet (Lopez 172). From this modest Himalayan outpost, the Dalai Lama not only rebuilt a scattered and traumatised community but also redefined Tibetan identity in exile. His leadership was rooted in the principles of non-violence (ahimsa), compassion (karuṇā), and universal responsibility (spyi’i drang ba), which soon resonated beyond the Tibetan borders.

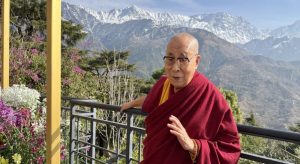

On 30 April 1990, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama arrived in Dharamshala, which subsequently became his government residence in exile. File phot

His Holiness understood that for the Tibetan people to survive as a distinct culture, education and spiritual training had to be prioritized. Under his leadership, a host of institutions emerged, focusing not only on traditional monastic training but also on secular education, interreligious dialogue, and international cooperation. The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA), established in 1970, stands as one of the most important repositories of Tibetan culture and Buddhist knowledge outside of Tibet. Housing thousands of manuscripts, sacred texts, artworks, and oral histories, the LTWA plays a pivotal role in the preservation of the Tibetan language, heritage, and religious tradition (Gyatso, The Heart of the Buddha’s Path 121). Complementing the LTWA is the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics (IBD), founded in 1973, which trains monks and lay scholars in rigorous debate, logic, Madhyamaka philosophy, and ethics, continuing the Nālandā tradition of Buddhist scholasticism. The IBD provides a curriculum that integrates classical Tibetan teachings with modern subjects, enabling scholars to engage with contemporary global thought (Samuel 213). In addition to these academic centers, numerous monasteries such as Namgyal Monastery (the personal monastery of the Dalai Lama), Gyuto Tantric Monastery, and Nechung Monastery were re-established in Dharamshala, creating a thriving spiritual environment. These institutions serve as both centers of learning and symbols of Tibetan resilience in exile.

Dharamshala is not merely a physical refuge; it is a moral landscape. The town has become a center of global activism grounded in Buddhist ethics. It is from here that the Dalai Lama has carried his message of compassion, dialogue, and non-violence to over sixty nations. He has participated in interfaith forums, scientific conferences, and political summits, meeting world leaders such as Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, and Pope John Paul II. These engagements illustrate his transformation into a transnational moral authority, unbound by territory but rooted in tradition. His teachings consistently emphasize “universal responsibility”, the idea that personal happiness and global peace are inseparably linked. As he explains, “We need to think of humanity as a whole. If we are to meet the challenges of our time, we must cultivate a sense of universal responsibility” (Dalai Lama, Ethics for the New Millennium 28). Dharamshala, therefore, serves not only as the spiritual nerve center of the Tibetan diaspora but also as a philosophical staging ground for a new global ethics. The Dalai Lama’s initiative in promoting secular ethics, which transcends religious boundaries, is now being incorporated into school curriculums in India and abroad. Institutions like the Dalai Lama Center for Ethics and Transformative Values at MIT are directly inspired by this vision (Thurman 93). These programs often draw on Buddhist ideas of mindfulness, empathy, and interdependence, but they are framed in universal human terms to appeal to a wider audience.

A less discussed but equally critical aspect of the Dalai Lama’s vision for Dharamshala is ecological stewardship. His concern for environmental balance is rooted in Buddhist principles of pratītyasamutpāda (theory of dependent origination) and ahiṃsā (non-harming). “Taking care of our environment is like taking care of ourselves,” he has repeatedly stated (Dalai Lama, Our Only Home 44). Several initiatives, including forest preservation, waste management programs, and sustainable tourism, have taken root in the region as a result of this ethos. Culturally, the preservation of Tibetan art, music, dance, and medicine is actively encouraged through institutions such as the Norbulingka Institute, which trains artisans and preserves endangered forms of Tibetan expression. It complements the spiritual infrastructure of Dharamshala by reinforcing Tibetan identity through culture and craftsmanship (Kapstein 204).

Reinvigorating Indian Sacred Heritage and Nālandā Tradition

Although the Dalai Lama is a Tibetan spiritual leader, his role in revitalising Indian Buddhism is monumental. After arriving in India in 1959, he found a land where Buddhism, once flourishing under emperors like Aśoka and Harṣa, had largely vanished as a living tradition. Recognising this loss, he took it upon himself to reintroduce the Buddha’s teachings to the Indian public, not merely as an ancient legacy but as a living path. His presence in India has reawakened national interest in the Buddha’s heritage. His Holiness reminded Indians of their deep historical connection with the Buddha, Nālandā University, and the legacy of great philosophers like Nāgārjuna, Asaṅga, and Dharmakīrti. Repeatedly emphasising that “India is the guru, Tibet the disciple, but today, the disciple has kept the teachings alive, while the guru has forgotten them”, he has initiated translation projects, established monasteries and cultural centers, and encouraged young Indians to study Buddhist philosophy (Dalai Lama, The Heart of the Buddha’s Path 134). His teachings in Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, and other pilgrimage sites have drawn not only monastics but also lay Indian followers, rekindling the relevance of Buddhism in Indian spiritual life. His solidarity with India’s neo-Buddhist communities, especially Dalits inspired by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, has also helped Buddhist identity grow among marginalised populations seeking dignity, empowerment, and spiritual meaning. His visits to Nagpur, Sarnath, Bodh Gaya, and other sacred sites reinforce the message that Buddhism is a shared spiritual heritage of the Indian subcontinent. His regular teachings at these pilgrimage sites have drawn thousands of Indian devotees, monastics, and international followers.

In response, His Holiness has encouraged the study of Nālandā texts, the revival of monastic education, and the translation of Tibetan scriptures into Sanskrit and Hindi (Gyatso, The Heart of the Buddha’s Path 134). He further established institutions in India viz. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives and the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies in Sarnath, which at present serve as centers for academic and spiritual training, are instrumental in preserving and propagating the Indo-Tibetan Buddhist tradition rooted in the Nālandā lineage, including the works of Nāgārjuna, Asaṅga, Dignāga, and Dharmakīrti (Thurman 122). By rekindling interest in Indian Buddhist philosophy, ethics, and soteriology, His Holiness has reconnected India with its ancient spiritual wisdom and shown that the message of the Buddha still speaks powerfully to modern challenges.

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is globally known as the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, a Nobel laureate, and a global advocate for non-violence and universal ethics. What is less widely acknowledged, but of profound significance, is his enduring commitment to the Nālandā tradition, the ancient Indian monastic university that became the cradle of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna philosophy. For the Dalai Lama, Nālandā is not merely a historical institution but a living tradition that forms the backbone of Tibetan Buddhism and provides a rational, analytical framework for both personal liberation and global harmony. Nālandā University flourished between the 5th and 12th centuries CE in present-day Bihar, India. It attracted students from across Asia, China, Tibet, Korea, and beyond. At its peak, it was home to thousands of monks and scholars who studied not only Buddhist philosophy and logic but also medicine, linguistics, and the arts. Its most revered masters, including Nāgārjuna, Asaṅga, Dignāga, Dharmakīrti, Śāntarakṣita, and Candrakīrti, authored texts that remain foundational in Buddhist scholasticism (Samuel 65). The curriculum at Nālandā emphasised rigorous dialectical reasoning (pramāṇa), debate, and ethical conduct, an approach His Holiness considers vital for the survival of Buddhism in the modern world. In his view, these methods are compatible with scientific inquiry and human rationality. “We follow the tradition of Nālandā,” the Dalai Lama asserts, “which is based on reasoning and investigation, not blind faith” (Dalai Lama, The Universe in a Single Atom 37).

When the Dalai Lama arrived in India in 1959 after fleeing Tibet, one of his foremost concerns was the preservation of the Nālandā-based Tibetan scholastic tradition. The Chinese invasion of Tibet had resulted in the destruction of numerous monasteries, and with them, centuries of transmission. Dharamshala, the seat of the Central Tibetan Administration, became the new ground where this legacy would be revived and re-contextualised. He supported the re-establishment of monastic universities such as Sera, Drepung, and Ganden in South India, which continued the Nālandā curriculum with its emphasis on Madhyamaka (Middle Way), Yogācāra (Mind-Only), epistemology, and logic. Meanwhile, the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics in Dharamshala was established to train a new generation of scholars grounded in Nālandā principles (Gyatso 122). To this day, Tibetan monks undergo 15-20 years of study in these monastic institutions, culminating in the Geshe degree, equivalent to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy. Their training includes the study of Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, Dharmakīrti’s Pramāṇavārttika, and Candrakīrti’s Madhyamakāvatāra. His Holiness regularly emphasises the necessity of understanding these texts through debate and logic, rather than devotion alone (Lopez 198).

A defining aspect of the Dalai Lama’s promotion of the Nālandā tradition is his effort to extract its universal components, ethics, logic, and psychology, for secular application. In his works such as Beyond Religion and Ethics for the New Millennium, he underscores the value of compassion, altruism, and interdependence as human, not exclusively religious, values. He advocates for an “education of the heart,” where analytical meditation (vipaśyanā) and contemplative science derived from Nālandā are integrated into modern education systems (Dalai Lama, Beyond Religion 45). The framework of secular ethics is influenced directly by the Nālandā view that mental afflictions can be eradicated through reasoning and practice. “Just as Nālandā masters taught, we can change the mind through training,” he notes (Dalai Lama, The Art of Happiness 52). These teachings have inspired educational institutions like the Dalai Lama Center for Ethics at MIT and programs on contemplative studies in universities across the globe. By rooting ethics in Nālandā logic rather than in divine authority, the Dalai Lama makes moral development accessible across cultures and beliefs. His Holiness’s interest in science, especially neuroscience, quantum physics, and cosmology, also springs from the Nālandā emphasis on critical inquiry. He frequently states that Buddhism must evolve by assimilating scientific discoveries, and if any aspect of Buddhist cosmology contradicts evidence, it must be reconsidered (Dalai Lama, The Universe in a Single Atom 7). This approach led to the founding of the Mind and Life Institute, which brings together scientists and contemplatives in dialogue. Buddhist models of consciousness, developed by Nālandā thinkers like Dignāga and Dharmakīrti, have proven especially fertile ground for scientific study of attention, emotion, and mental training (Davidson and Goleman 84). The integration of Nālandā psychology with contemporary science has helped build a new language for understanding the mind, one that honors both rational insight and inner experience.

The Dalai Lama’s invocation of Nālandā is not limited to religious or academic settings. It has become a symbol of India’s Buddhist past and its potential for spiritual leadership. He often reminds Indian audiences: “India is the guru; Tibet is the disciple. We Tibetans preserved your knowledge; now it is time to bring it home” (Thurman 116). His call has resonated with Indian policymakers, leading to increased efforts to revive Buddhist scholarship and pilgrimage infrastructure, including the restoration of Nālandā University. For Tibetans, the Nālandā tradition represents cultural continuity and intellectual autonomy. For the global audience, it signifies a fusion of science, ethics, and spirituality. For Indians, it is a reclaiming of a luminous chapter in their philosophical heritage. For the 14th Dalai Lama, the Nālandā tradition is not a relic of the past but a timeless resource for the future of humanity. It embodies an approach to spirituality grounded in logic, ethical clarity, and psychological transformation. Whether through rigorous scholasticism, compassionate ethics, or scientific inquiry, His Holiness continues to keep the Nālandā flame alive, not only in monasteries but in classrooms, parliaments, laboratories, and public discourse. In a world fragmented by dogma and division, the Dalai Lama’s commitment to the Nālandā ideal offers a vision of unity grounded in shared humanity and rational compassion.

Concluding Remark

As we mark the 90th birthday of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, we do not merely celebrate a personal milestone, we celebrate a global legacy. From the snow-covered peaks of Tibet to the halls of the United Nations, from monasteries in Dharamshala to neuroscience labs in California, his life has bridged the ancient and the modern, the mystical and the rational. His teachings have touched countless lives, emphasising that true change begins from within and that compassion, when practiced sincerely, has the power to reshape our world. As he often reminds his followers, “Our prime purpose in this life is to help others. And if you can’t help them, at least don’t hurt them.” In a world increasingly defined by division, His Holiness remains a unifying presence, a living legend who speaks not only for the Tibetan people but for all of humanity. The legacy is vast and enduring and in the face of adversity, he has embodied the transformative power of compassion and resilience. As the world looks to uncertain times, the Dalai Lama remains a beacon of hope and moral clarity, a living legend whose light continues to shine across borders, faiths, and generations. His Holiness’s greatest gift to the modern world may be his ability to universalise the teachings of Buddhism. Grounded in the Four Noble Truths, the Bodhisattva ideal, and Nālandā traditions of logic and reason, his interpretation of Buddhism is deeply rational, accessible, and ethically grounded. “My religion is very simple,” he once remarked. “My religion is kindness” (Dalai Lama, The Art of Happiness 19). His books, including Ethics for the New Millennium, The Universe in a Single Atom, and The Art of Happiness, are not merely spiritual manuals but moral compasses. They offer profound insights into how individuals and societies might foster peace, develop resilience, and cultivate compassion in an increasingly polarised world. His global appeal is evident in the flourishing of Tibetan Buddhist centers across North America, Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Lay practitioners and scholars alike find resonance in his vision of inner transformation as a basis for social reform.

Dharamshala’s importance extends well beyond the Tibetan refugee community. For followers of Buddhism around the world, especially in the West, it has become a pilgrimage site and a place of spiritual renewal. Visitors from countries such as the United States, Japan, Germany, and Brazil come to study meditation, engage in dialogues, or attend public teachings by His Holiness. These events are often conducted in open settings, with thousands gathered in the Tsuglagkhang Complex, the main temple adjacent to the Dalai Lama’s residence. Translated simultaneously into multiple languages, these teachings exemplify the democratisation of sacred knowledge and the Dalai Lama’s commitment to global education (Lopez 189). Dharamshala is also home to non-Tibetan Buddhist practitioners who have become ordained under the Tibetan tradition. Notable figures such as Pema Chödrön, Matthieu Ricard, and Thubten Chodron have studied and taught here, bridging East-West spirituality and ensuring that Tibetan Buddhism continues to evolve while remaining grounded in its core tenets (Davidson and Goleman 72). Additionally, Dharamshala has become a global symbol of peaceful resistance. The CTA functions not only as a governmental body in exile but also as a model for non-violent struggle. Its democratic structure, transparent electoral processes, and emphasis on dialogue over confrontation have garnered international respect (Tibetan Government in Exile 12). Dharamshala, under the spiritual and ethical guidance of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, has evolved from a colonial-era cantonment into a living mandala, a sacred geography where exiled traditions, global dialogue, and spiritual renewal converge. It serves as both a sanctuary and a platform, where Tibetan culture is preserved, Buddhist teachings are propagated, and universal values are promoted on the world stage. More than just a refuge for displaced people, Dharamshala has become a model of how spiritual resilience can foster cultural rebirth and moral leadership. It is a place where the past is honored, the present is engaged, and the future is envisioned with compassion and courage. For Buddhists, peace advocates, and seekers worldwide, Dharamshala stands as a luminous karmabhūmi, sanctified not by conquest but by compassion.

References:

- Bansal, Sunita. Himalayas: Mountains of Life. Wisdom Tree, 2012.

- Dalai Lama. Ethics for the New Millennium. Riverhead Books, 1999.

- —. Our Only Home: A Climate Appeal to the World. Hanover Square Press, 2020.

- Davidson, Richard J., and Daniel Goleman. Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body. Avery, 2017.

- Gyatso, Tenzin. The Heart of the Buddha’s Path. Thorsons, 1995.

- Kapadia, Harish. Into the Untravelled Himalaya: Travels, Treks, and Climbs. Indus Publishing, 2005.

- Kapstein, Matthew. The Tibetans. Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- Lopez, Donald S. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West. University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Samuel, Geoffrey. Introducing Tibetan Buddhism. Routledge, 2012.

- Thurman, Robert A. F. Why the Dalai Lama Matters: His Act of Truth as the Solution for China, Tibet, and the World. Atria Books, 2008.

- Tibetan Government in Exile. The Middle Way Approach: A Framework for Resolving the Issue of Tibet. Central Tibetan Administration, 2010.

By Prof (Dr) Arvind Kumar Singh

Visiting Professor, ICCR Chair

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Chair for Buddhist Studies

Lumbini Buddhist University, Lumbini, Nepal

&

School of Buddhist Studies and Civilisation

Gautam Buddha University, India

Email: aksinghdu@gmail.com; arvinds@gbu.ac.in