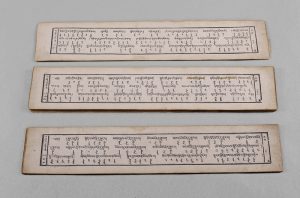

A book called “Merged Garakhyn Oron” was compiled in 1741-1742 by a group of scholars led by Janjaa Rolbidorj in order to translate terms and terminologies in the Danjuur or Tengyur, which is the Tibetan collection of commentaries to Buddha’s teachings, or the “Translated Treatises”.

In the history of Mongolian lexicography, there are many bilingual Tibetan-Mongolian dictionaries and as well as trilingual Sanskrit, Tibetan and Mongolian dictionaries. The tradition of composing the dictionaries in Mongolian has the same Indian source as the origination of Buddhism. It was not only the religion that was borrowed but a lot of cultural phenomena as well. The Tibetans were the first to accept Buddhism and from there it spread among the Mongols.

Actually, much earlier there was a short period of a strong Yugourian influence on the Mongols and their first acquaintance with Buddhism they got from the Yugours. But the period was short and first wave of Buddhism doesn’t have a direct connection with the Tibetan-Mongolian dictionaries the subject of the present presentation. Though it is well-known that a lot of key words (such as bodhisattva, sutra, dharani, etc.) were borrowed from Sanskrit at the time. They were accepted by the Mongolian language and were preserved there. Well-preserved because centuries later when translations from Tibetan into Mongolian were made it were these Sanskrit words that were used to translate the Tibetan words. The Sanskrit epics and literature flourished long before there even was an alphabet in what is now Mongolia.

Leaves from the printed version of the famous Tibetan-Mongolian dictionary “A Lexicon Resource for the Learned” (Tib. dag-yig ,khas-pa’i ‘byung-gnas; Mong. Merged Garakhyn Oron), which was compiled in 1741-1742.

The tradition of composing lexicons was developed further. The best known and a real masterpiece among them is the Amarakośa dictionary written by Amarasiṁgha (8th century A.D.). In the 13th century, it was translated into Tibetan by Kirtichandra and Grags pa rgyal mtshan, and was edited first by Chos skyong bzang po (1441-1528) then later by gTsug lag chos kyi snang ba or Situ Panchen (1699-1779). This work is written in verse and it has a lot of synonyms organized as lists referring to different referents. The primary interest to us here is that this lexicon was translated into Tibetan, three translations are known (one of them was published facsimile by prof. Lokesh Chandra. The Amarakośa lexicon had a great influence on Tibetan works of the same kind the most well-known is “The decoration of the wise man’s ears”. Amarasimha’s dictionary was translated into Tibetan verse from the Sanskrit original which is translated into Mongolian. In the volume 205 of the Mongolian Danjuur contains the translation of this dictionary by Mongolian translator Geleggyaltsan. Not a few words and expressions originally from Sanskrit lexicons were included into some Tibetan-Mongolian dictionaries.

The other famous dictionary called Mahāvyutpatti is a well-known and the basic lexicographical work often referred to as “A dictionary of Buddhist terminology”. At least the aim of this work was to help the translation of Holy Scriptures. It was compiled in 801 or 812 in Tibet by a committee of Indian and Tibetan scholars for a special imperial order. The Mahāvyutpatti assumed a key role in the centrally decreed (bkas bcad) revision/redaction process (źu chen) designed to regularise current methods of translation. it was complemented by two other registers (vyutpatti) of similar function: the Madhyavyutpatti (Tib. sGra sbyor bam (po) gñis (pa)) and *Svalpavyutpatti (Tib. Bye brag tu rtogs byed chuṅ ṅu). Of the three, the Mahavyutpatti is best understood and the translation into Mongolia was made during the revival of Buddhism in Mongolia in 17th and early 18th centuries which was under the leadership of Jangya Rolby Dorjee. Far as two translations were made into Mongolian. The first is included in Tengyur, the second is a manuscript preserved at the library of Oriental Faculty in St. Petersburg State University. It was published facsimile in 1859 in St. Petersburg by A. Schiefner who called it “Die Buddhistische Triglotte” and it has been known under this title since, for it does not have any title of its own. It is a text from the collection of baron Schilling von Canstadt (as a handwritten inscription says). A. Schiefner writes in the Introduction to his publication that it is the same as a Beijing edition – the Buddistishe Pentaglotte. It was published by Alice Sárközi with the English translation (1995).

The Mahāvyutpatti is often called not a dictionary but an encyclopedia, which (as Csoma de Kőrös wrote in one of the letters: “…highly interesting to understand better the whole system and principles of the Buddhist doctrine”. (I’m quoting the preface to the edition of Mongolian translation made by A. Sárcösi). Whatever we call it (a lexicon, a dictionary or an encyclopedia) the Mahāvyutpatti is a great work. The most important about it was that it represented the undisputable Tibetan terminology for translating Sanskrit texts into Tibetan. It is organized according to the traditional for that period Indian subject pattern. It is divided into paragraphs (or chapters), 277 of them, the number of words and expressions in one chapter can vary from two to hundreds and about two thirds of the dictionary is connected with Buddhism. The total number of entries is about 9500. If you compare the Amarakośan and Mahāvyutpati, you’ll see that the backbone order of the subjects is the same.

Also, a copy of the Pentaglotte dictionary is preserved in the collection of St. Petersburg Institute as well. Both have 71 chapters and about 1000 entries. The difference is that the Triglotte has three languages (Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian) and Pentaglotte has five (Manchu and Chinese are added). Sanskrit in both dictionaries is written in Tibetan letters. Neither of two texts has a colophone, so there is no information about the author and the date. As for the Second Changkya Khutukhtu he is known to be the leading author of another Tibetan-Mongolian dictionary: A Lexicon Resource for the Learned (Tib. Dag-yig mkhas-pa’i ‘byung-gnas, Mong. Merged garah-yin oron).

The Triglotte and Penaglotte being compared, show that their Sanskrit, Tibetan and Mongolian texts are identical. The both dictionaries have only tiny differences and identical mistakes in the Sanskrit part. Also, it’s difficult to say which of the two dictionaries appeared the first and which is the copy but these two are identical enough for comparing them as a whole with Mahāvyutpatti.

The Mahāvyutpatti has 277 chapters, Triglotte has 71 chapters. Triglotte of course is shorter and not all chapters from Mahāvyutpatti were included in it.

An early 9th century Tibetan dictionary of Sanskrit Buddhist terminology containing 9,565 lexical items arranged thematically into 277 chapters. The work was devised partly as a means of standardizing translations from Sanskrit into Tibetan. Later versions of this text were produced in the 17th century with Chinese, Mongolian, and Manchurian equivalents added.

One of the hand written Mahāvyutpatti which called Quadrilingual Mahāvyutpatti has in four languages (Sanskrit-Tibetan-Chinese-Mongolian), it’s published in SATA-PITAKA series volume 277 and another Penaglotte was published in SATA-PITAKA series volume 19 which is written in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian and Chinese that edited by prof. Raghuvira and prof. Lokesh Chandra as well.

Acharya Testsee Luvsandorj,

Zanabazar Buddhist Monastery,

Gandan Tegchenling Monastery,

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.